In researching this recording of works by Liszt from 1848 to 1867, one of the most turbulent periods of the 19th century, I was fascinated to learn how Liszt had formed and maintained friendships with so many major figures of his time, and put my reflections into the original program notes of the CD. Now that the CD has been re-edited in a new downloadable form by B.I.P. and available almost everywhere from Itunes to emusic, my only regret was that these reflections may be lost in the process. Remember the days when we would pore over the jackets of long-playing 33 rpm… For short-sighted people like myself, even CDs quickly lost this abiity to complement one’s listening pleasure: where are my glasses? The size of a computer screen is a little like those old LP jackets. So one of the things I wanted on this new site was to post those original program notes, now illustrated, as an incentive to buy my recording (of course!), but more especially as an invitation to explore the context of this music at your own leisure. Listen to Liszt’s Liebestraum no 1 as a bonus for getting this far.

LISZT – JEFFREY GRICE

1 Les Sabéennes (GOUNOD-LISZT) 03:49

2 Rêve d’amour n° 2 “Seliger Tod” 03:20

3 Vallée d’Obermann 12:20

4 Rêve d’amour n° 1 “Hohe Liebe” 05:10

5 Les Adieux (GOUNOD-LISZT) 07:59

6 Ballade n° 2 en si mineur 14:00

7 Consolation n° 1 01:13

8 Consolation n° 2 02:46

9 Consolation n° 3 03:13

10 Consolation n° 4 02:22

11 Consolation n° 5 02:02

12 Consolation n° 6 03:05

13 Rêve d’amour n° 3 “O Lieb” 03:47

14 Hymne à Sainte Cécile (GOUNOD-LISZT) 09:01

TOTAL LENGTH: 74:34

“A BRIGHT GENIUS”

In 1847, after an eight-year stint of incessant touring, Franz Liszt (1811-1886), already a legend throughout Europe at the age of thirty-six, renounced what must have been one of the greatest piano-playing careers of all time, to become Kappellmeister at the court of Weimar. Giving up such success today would be almost unthinkable. Yet Liszt’s nature was a generous one. From that point on, he was to compose and perform other composers, becoming one of the foremost advocates of Wagner, programming operas (even mini-festivals) of his other contemporaries Berlioz, Schumann, Saint-Saëns, and working perhaps more than any other nineteenth-century musician for the propagation of the music of his day.

On July 20th, 1854, two Georges, Marian Evans (alias George Eliot, left) and George Lewes , her “partner”, a somewhat unconventional relationship for Victorian England, left London for the Continent, arriving in Weimar, the “Athens of the north” on August 2nd. Lewes, who was preparing a biography of Goethe, had known Liszt in Vienna in 1839 and called on him on August 9th. The maestro quite informally came over to where they were staying the following day at half-past ten, chatted for a while and invited them to breakfast at the Altenburg where he was living openly with the Princess Caroline Sayn-Wittgenstein, his “mystic Amazon”(in his own words), who had followed him to Weimar and whose husband was soon to divorce her. Eliot’s impressions of this first meeting can be found in her correspondence:

On July 20th, 1854, two Georges, Marian Evans (alias George Eliot, left) and George Lewes , her “partner”, a somewhat unconventional relationship for Victorian England, left London for the Continent, arriving in Weimar, the “Athens of the north” on August 2nd. Lewes, who was preparing a biography of Goethe, had known Liszt in Vienna in 1839 and called on him on August 9th. The maestro quite informally came over to where they were staying the following day at half-past ten, chatted for a while and invited them to breakfast at the Altenburg where he was living openly with the Princess Caroline Sayn-Wittgenstein, his “mystic Amazon”(in his own words), who had followed him to Weimar and whose husband was soon to divorce her. Eliot’s impressions of this first meeting can be found in her correspondence:

“Liszt is the first really inspired man I ever saw. His face might serve for a model of St. John. All sweetness in repose, when seated at the piano, Liszt is as grand as one of Michelangelo’s prophets. When I read George Sand’s letter to Franz Liszt in her Lettres d’un voyageur, I little thought that I should ever be seated in tête-à-tête with him for an hour as I was yesterday, telling him my thoughts and feelings.”…

“Liszt is the first really inspired man I ever saw. His face might serve for a model of St. John. All sweetness in repose, when seated at the piano, Liszt is as grand as one of Michelangelo’s prophets. When I read George Sand’s letter to Franz Liszt in her Lettres d’un voyageur, I little thought that I should ever be seated in tête-à-tête with him for an hour as I was yesterday, telling him my thoughts and feelings.”…

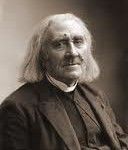

“Then came the thing I so longed for – Liszt’s playing. I sat near him so that I could see both his hands and face. For the first time in my life I beheld real inspiration – for the first time I heard the true tones of the piano. He played one of his own compositions – one of a series of religious fantasies. There was nothing strange or excessive about his manner. His manipulation of the instrument was quiet and easy, and his face was simply grand – the lips compressed and the head thrown a little backward. When the music expressed quiet rapture or devotion, a sweet smile flitted over his features: when it was triumphant the nostrils dilated. There was nothing petty or egotistic  to mar the picture. Why did Scheffer not paint him thus, instead of representing him as one of the three Magi?” (left, Liszt photographed in later life by Nadar) This was Eliot’s first glimpse of the transcendent artist. Liszt is “a glorious creature in every way – a bright genius, with a tender, loving nature and a face in which this combination is perfectly expressed.” She says that he had a divine ugliness (“laideur divinisée”) “by which the soul gleams through, my favorite kind of physique.”

to mar the picture. Why did Scheffer not paint him thus, instead of representing him as one of the three Magi?” (left, Liszt photographed in later life by Nadar) This was Eliot’s first glimpse of the transcendent artist. Liszt is “a glorious creature in every way – a bright genius, with a tender, loving nature and a face in which this combination is perfectly expressed.” She says that he had a divine ugliness (“laideur divinisée”) “by which the soul gleams through, my favorite kind of physique.”

During the couple of months they remained in Weimar, the “Lewes” were soon on intimate terms with the “Liszts”. A connection that was to continue, for when Wagner came to London in 1877 to conduct concerts in the Albert Hall, his wife, Liszt’s daughter Cosima, came with a letter of introduction from her father to Eliot who was subsequently close to Wagner also.

1. Les Sabéennes (GOUNOD-LISZT)

The first performance of Gounod’s opera La reine de Saba (The Queen of Sheba), was given at the Paris Opera on February 28th, 1862. Not as successful as Faust (1859) or as was to be Roméo et Juliette (1867), it must have nevertheless pleased Liszt who made this arrangement between 1862 and 1865 of the third movement of the Ballet from Act IV, sc.2.

2. Notturno II – Seliger Tod (Dream of love n° 2)

Originally conceived for tenor and piano accompaniment, the 3 Liebesträume, composed in 1850, were in fact published as solo piano pieces with poetic texts printed as a forward. In the first two, appear texts by the German poet Ludwig Uhland (1787-1862), also a prominent politician of the day. His sets of Ballads, the best of his poetry, have the aspect of popular songs:

Gestorben war ich vor Liebeswonne, Begraben lag ich in ihrem Armen. Erwecket ward ich von ihren Küssen, den Himmel sah ich In ihren Augen.

I perished from the joys of love, lying buried in your arms. Aroused by your kisses, I saw heaven in your eyes

3. Vallée d’Obermann

Liszt wrote this masterpiece as part of the Années de pélèrinage en Suisse, first published in 1855, the longest of nine pieces which evoke his stay in Switzerland some twenty years before with Marie d’Agoult. On the flyleaf of the edition Liszt prints extracts from two literary works : de Senancour’s Obermann and Byron’s Childe Harold.

Etienne Pivert de Senancour (1770-1846) was influenced by Rousseau in writing Obermann (1804), less a novel than a long complaint about the bitterness of life, about how, despite the exaltation of the natural world and intellectual passion that make one keen to enlighten one’s fellow-man, the artist is doomed to despair. An unhappy marriage only aggravating his ambient pessimism, de Senancour regrets a sickness of will that prevents him from becoming a “superman” (the sense of Obermann):

Etienne Pivert de Senancour (1770-1846) was influenced by Rousseau in writing Obermann (1804), less a novel than a long complaint about the bitterness of life, about how, despite the exaltation of the natural world and intellectual passion that make one keen to enlighten one’s fellow-man, the artist is doomed to despair. An unhappy marriage only aggravating his ambient pessimism, de Senancour regrets a sickness of will that prevents him from becoming a “superman” (the sense of Obermann):

“What do I want? What am I? What can I ask of nature? Every cause is invisible, every end illusory, every form changeable, every length fatiguing… I feel I exist to consume myself in indomitable desires, drinking in the seductiveness of a fantastic world only to be appalled by its voluptuous delusion.” Senancour, Obermann – Letter 53

Could I embody and unbosom now that which is most within me, could I wreak my thoughts upon expression, and thus throw soul, heart, mind, passions, feelings, strong or weak, all that I would have sought and all I seek, bear, know, feel, and yet breathe, – into one word, and that one word were lightning, I would speak: but as it is, I live and die unheard, with a most voiceless thought, sheathing it as a sword.

Could I embody and unbosom now that which is most within me, could I wreak my thoughts upon expression, and thus throw soul, heart, mind, passions, feelings, strong or weak, all that I would have sought and all I seek, bear, know, feel, and yet breathe, – into one word, and that one word were lightning, I would speak: but as it is, I live and die unheard, with a most voiceless thought, sheathing it as a sword.

Lord Byron, Childe Harold

4. Notturno I – Hohe Liebe (Dream of love n° 1)

Another Ballad by the German poet Ludwig Uhland (left) is included as a preface to the first of the Liebesträume. The two poets chosen by Liszt for his dreams of love (Uhland and Freiligrath) both also had an intense political commitment to social renewal. Written in 1850, after the dramatic events of the Revolution of 1848, perhaps Liszt’s pieces have more to do with shattered dreams of love for one’s fellowman than with erotic passion? Listen to Liebestraum no 1.

Another Ballad by the German poet Ludwig Uhland (left) is included as a preface to the first of the Liebesträume. The two poets chosen by Liszt for his dreams of love (Uhland and Freiligrath) both also had an intense political commitment to social renewal. Written in 1850, after the dramatic events of the Revolution of 1848, perhaps Liszt’s pieces have more to do with shattered dreams of love for one’s fellowman than with erotic passion? Listen to Liebestraum no 1.

In Liebesarmen ruht ihr trunken, des Lebens Früchte winken euch. Ein Blick nur ist auf mich gesunken,doch bin ich vor euch allen reich. Das Glück der Erde miss ich gerne und blick, ein Märtyrer, hinan, denn über mir in goldner Ferne Hat sich der Himmel aufgetan

Drunk in the arms of love among the appealing fruits of life, a single look has chosen me and makes me rich in all. I can do without earthly success for I, a martyr, lift my eyes upwards to golden splendors in the heavens.

5. Les Adieux – Rêverie sur un motif de l’opéra de Charles Gounod Roméo et Juliette (GOUNOD-LISZT)

Roméo et Juliette, a major operatic success of Gounod (left), was premiered on April 27th, 1867. Liszt wrote this fantasia in the same year. The scene of farewell (in Act III of Shakespeare’s play) is the last time the lovers will converse… Romeo: I have more care to stay than will to go. Come death and welcome! Juliet wills it so. How is’t, my soul? Let’s talk – it is not day. Juliet: It is, it is; hie hence, be gone, away! It is the lark that sings so out of tune, straining harsh discords and unpleasing sharps… O God, I have an ill-divining soul! Methinks I see thee, now that are below, As one dead in the bottom of a tomb; Either my eyesight fails or thou look’st pale. Romeo: And trust me, love, in my eye so do you; Dry sorrow drinks our blood. Adieu, adieu!

Roméo et Juliette, a major operatic success of Gounod (left), was premiered on April 27th, 1867. Liszt wrote this fantasia in the same year. The scene of farewell (in Act III of Shakespeare’s play) is the last time the lovers will converse… Romeo: I have more care to stay than will to go. Come death and welcome! Juliet wills it so. How is’t, my soul? Let’s talk – it is not day. Juliet: It is, it is; hie hence, be gone, away! It is the lark that sings so out of tune, straining harsh discords and unpleasing sharps… O God, I have an ill-divining soul! Methinks I see thee, now that are below, As one dead in the bottom of a tomb; Either my eyesight fails or thou look’st pale. Romeo: And trust me, love, in my eye so do you; Dry sorrow drinks our blood. Adieu, adieu!

Liszt actually chose three motifs from Gounod’s opera (not only one as stated in the title) to catch the spirit of the work with more poignancy.

6. Ballade n° 2 in B minor

Composed in 1853 soon after the Sonata, Liszt’s Ballade n° 2 is also a dramatic single-movement work, remarkable in the way its three themes are continually transformed. Liszt, deeply involved in the society of his day, would have been profoundly affected by the events of the 1848 Revolution in Europe. Many of his close friends had lost their lives. This work is dedicated posthumously to Count Karoly Leiningen (left), executed in October 1849 as one of the thirteen leaders of the Hungarian uprising. Sacheverell Sitwell felt it evoked “great happenings of the epical scale, barbarian invasions, cities in flames – tragedies of public, more than private, import.”

Composed in 1853 soon after the Sonata, Liszt’s Ballade n° 2 is also a dramatic single-movement work, remarkable in the way its three themes are continually transformed. Liszt, deeply involved in the society of his day, would have been profoundly affected by the events of the 1848 Revolution in Europe. Many of his close friends had lost their lives. This work is dedicated posthumously to Count Karoly Leiningen (left), executed in October 1849 as one of the thirteen leaders of the Hungarian uprising. Sacheverell Sitwell felt it evoked “great happenings of the epical scale, barbarian invasions, cities in flames – tragedies of public, more than private, import.”

7. – 12. Les 6 Consolations

These six pieces, composed around 1850, imbued with a melancholy and fervent devotion, were inspired by a collection of poems by Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve (1804-1869) of the same title,  anonymously published in 1830. Sainte-Beuve (left) had been interested, like Liszt, in the socialist principles of Saint-Simon and at the time of his Consolations had put much hope in a renewal of Catholic liberalism. But after the papal bull of 1832 suppressing this renewal, Sainte-Beuve, disappointed, would gradually fall away from the Church and move into politics. Liszt’s Consolations , twenty years later, were a mark of sympathy on his part for what Sainte-Beuve represented.

anonymously published in 1830. Sainte-Beuve (left) had been interested, like Liszt, in the socialist principles of Saint-Simon and at the time of his Consolations had put much hope in a renewal of Catholic liberalism. But after the papal bull of 1832 suppressing this renewal, Sainte-Beuve, disappointed, would gradually fall away from the Church and move into politics. Liszt’s Consolations , twenty years later, were a mark of sympathy on his part for what Sainte-Beuve represented.

13. Notturno III – O Lieb (Dream of love n° 3)

The third of the Liebesträume is accompanied by a text of Ferdinand Freiligrath (1810 – 1876). When George Eliot met Liszt, they communicated in French. George Eliot had begun her writing  career with translations from German into English. Freiligrath (left), another well-travelled European, was the translator of Alfred de Musset, Victor Hugo, Tennyson and Longfellow. Active politically, he collaborated with Karl Marx on the Rheinische Zeitung in 1848 in Cologne, from where he was exiled in 1849 when the newspaper was banned. Liszt would have been aware of these circumstances when he published his Liebesträume in 1850.

career with translations from German into English. Freiligrath (left), another well-travelled European, was the translator of Alfred de Musset, Victor Hugo, Tennyson and Longfellow. Active politically, he collaborated with Karl Marx on the Rheinische Zeitung in 1848 in Cologne, from where he was exiled in 1849 when the newspaper was banned. Liszt would have been aware of these circumstances when he published his Liebesträume in 1850.

O lieb, o lieb so lang du lieben kannst, so lang du lieben magst. Die Stunde kommt, wo du an Gräbern stehst und klagst. Und sorge dass dein Herz glüht, und Liebe hegt und Liebe trägt.So lang ihm noch ein ander Herz in Liebe warm entgegenschlägt. Und wer dir seine Brust erschliesst, o tu ihm was du kannst zu Lieb und mach ihm jede Stunde froh, und mach ihm keine Stunde trüb! Und hüte deine Zunge wohl : bald ist ein hartes Wort entflohn. O Gott – es war nicht bös gemeint – Der andre aber geht und weint.

Love, love as long as you can, as long as you may, for the hour is coming when you will regret the grave. Let your heart shine, cherish your love and let it come to fruition, as long as another heart comes to warm itself in your love. And whoever reveals his inmost soul to you, do what you can to love him. Make him happy each hour, and never make him sad! And keep your tongue under control, a harsh word is so easily released. “Oh God – I didn’t mean to hurt” – Yet the other has already gone away to weep.

14. Hymne à Sainte Cécile (GOUNOD-LISZT)

In 1848, after having studied theology for five years, Charles Gounod (1818 -1893) was on the point of going into the priesthood. In 1861, Liszt, discontented by hostility from conservative forces in Weimar, gave up his post, went to settle in Rome, and himself took minor orders. In this hymn to  Saint Cecilia (left, painted by Pietro da Cortona), the patron saint of music, the marks of both composers are strongly in evidence. Gounod’s original piece for violin and piano was written in 1865, and Liszt’s transcription completed on June 3rd, 1866. Gounod’s work of 77 bars was enlarged to 160 in the course of the transcription. Liszt intended to have it published but must have let it out of his keeping somehow, for he writes in a letter dated Rome, January 20th, 1885 to the Countess Mercy-Argenteau (below, painted by Ilya Repin) : “An obstinate publisher has

Saint Cecilia (left, painted by Pietro da Cortona), the patron saint of music, the marks of both composers are strongly in evidence. Gounod’s original piece for violin and piano was written in 1865, and Liszt’s transcription completed on June 3rd, 1866. Gounod’s work of 77 bars was enlarged to 160 in the course of the transcription. Liszt intended to have it published but must have let it out of his keeping somehow, for he writes in a letter dated Rome, January 20th, 1885 to the Countess Mercy-Argenteau (below, painted by Ilya Repin) : “An obstinate publisher has  asked me again for my transcription of Gounod’s St Cécile. If you could find its manuscript among your old papers, be so kind to lend it to me for a fortnight so that it can be copied, printed and then returned to its most charming proprietor.” The manuscript was however not returned and only fairly recently published in the current Budapest comprehensive edition of Liszt’s works.

asked me again for my transcription of Gounod’s St Cécile. If you could find its manuscript among your old papers, be so kind to lend it to me for a fortnight so that it can be copied, printed and then returned to its most charming proprietor.” The manuscript was however not returned and only fairly recently published in the current Budapest comprehensive edition of Liszt’s works.

CREDITS

Sound engineer: Karim Saï, courtesy of Caravan

Recorded en 24 bits in the Studio of Didier Lockwood in Barbizon

Many thanks to Didier and Caroline, Karim and especially to Simonne

Dedicated to Shirley and Jim, over sixty years together

English and French presentations and translations of poems by Jeffrey Grice

“UN HEUREUX MELANGE”

En 1847, après huit années de tournées incessantes à travers l’Europe, le déjà légendaire Franz Liszt, à gauche (1811-1886) renonce à ce qui devait être l’une des plus grandes carrières de pianiste/virtuose de tous les temps, pour devenir Kappellmeister à la cour de Weimar. A partir de ce moment-là, cette nature fière et généreuse va composer mais aussi se consacrer à la musique de son temps comme personne d’autre. C’est lui qui dirigera plusieurs premières d’opéra dont Lohengrin de Wagner. Encore lui qui organise des Festivals Berlioz, ou défend la musique de ses contemporains Schumann ou Saint-Saëns…

En 1847, après huit années de tournées incessantes à travers l’Europe, le déjà légendaire Franz Liszt, à gauche (1811-1886) renonce à ce qui devait être l’une des plus grandes carrières de pianiste/virtuose de tous les temps, pour devenir Kappellmeister à la cour de Weimar. A partir de ce moment-là, cette nature fière et généreuse va composer mais aussi se consacrer à la musique de son temps comme personne d’autre. C’est lui qui dirigera plusieurs premières d’opéra dont Lohengrin de Wagner. Encore lui qui organise des Festivals Berlioz, ou défend la musique de ses contemporains Schumann ou Saint-Saëns…

En 1854, l’écrivain anglais George Eliot (de son vrai nom : Marian Evans) séjournait à Weimar  avec son compagnon George Lewes (à gauche) qui écrivait à l’époque une biographie sur Goethe. Le couple qui vivait ensemble ouvertement (Lewes étant déjà marié à quelqu’un d’autre) dans l’Angleterre victorienne quitte Londres pour l’air plus “respirable” du Continent, arrivant à Weimar, “l’Athènes du nord”, le 2 août. Lewes, qui avait rencontré Liszt à Vienne en 1839, lui rend visite le 9 août. Et c’est le maître lui-même qui arrive chez eux le lendemain vers 10h30 et bavarde pendant quelque temps avant de

avec son compagnon George Lewes (à gauche) qui écrivait à l’époque une biographie sur Goethe. Le couple qui vivait ensemble ouvertement (Lewes étant déjà marié à quelqu’un d’autre) dans l’Angleterre victorienne quitte Londres pour l’air plus “respirable” du Continent, arrivant à Weimar, “l’Athènes du nord”, le 2 août. Lewes, qui avait rencontré Liszt à Vienne en 1839, lui rend visite le 9 août. Et c’est le maître lui-même qui arrive chez eux le lendemain vers 10h30 et bavarde pendant quelque temps avant de  les inviter à prendre le petit déjeuner chez lui à l’Altenburg où il vit avec celle qu’il appelle son “amazone mystique”, la princesse Caroline Sayn-Wittgenstein (à gauche) qui l’a suivi à Weimar et que le mari va bientôt répudier. Les “Lewes” se rendent donc chez les “Liszt”. Voici comment parle George Eliot de cette matinée:

les inviter à prendre le petit déjeuner chez lui à l’Altenburg où il vit avec celle qu’il appelle son “amazone mystique”, la princesse Caroline Sayn-Wittgenstein (à gauche) qui l’a suivi à Weimar et que le mari va bientôt répudier. Les “Lewes” se rendent donc chez les “Liszt”. Voici comment parle George Eliot de cette matinée:

“Liszt est le premier homme véritablement inspiré que j’ai jamais rencontré. Son visage au repos pourra servir comme modèle pour le doux St Jean, mais assis au piano il est aussi grand qu’un prophète de Michel-Ange. A l’époque où j’avais lu la lettre de Georges Sand à Franz Liszt dans ses Lettres d’un voyageur, j’étais loin d’imaginer qu’un jour je serais assise en tête-à-tête avec lui pendant plus d’une heure, comme je l’étais hier, à lui raconter mes idées et mes sentiments.”…”Puis, est venu la chose que je désirais tant – Liszt s’est mis à jouer. Je me suis assise auprès de lui pour pouvoir observer ses mains et son visage. Pour la première fois de ma vie, j’ai contemplé l’inspiration pure – pour la première fois, j’ai entendu le vrai son du piano. Il a joué une de ses propres compositions – une espèce de fantaisie religieuse. Il n’y avait rien d’étrange ou d’excessif dans sa manière de jouer. Sa manipulation de l’instrument fut tranquille et facile, et son visage était tout simplement grandiose – les lèvres comprimées et la tête relevée un peu en arrière. Quand la musique exprimait du ravissement ou de la dévotion intime, un sourire doux lui traversait les traits du visage : quand elle devenait triomphante les narines dilataient. Rien de mesquin, rien d’égoïste ne venait gâcher l’image. Pourquoi Scheffer ne l’a pas peint ainsi, au lieu de le représenter comme l’un des Trois Mages?” C’était pour Eliot, son premier aperçu d’un artiste transcendant. Pour elle, Liszt est “une créature glorieuse à tous égards – un génie brillant d’une nature tendre et affectueuse avec un visage qui exprime parfaitement cet heureux mélange.” Ailleurs elle parle de sa “laideur divinisée, à travers laquelle l’âme transparaît, le genre de physique que je préfère.”

Pendant les quelques mois de leur séjour à Weimar, Eliot deviendra assez intime avec Liszt. Une amitié qui va durer longtemps, car quand Wagner viendra diriger sa musique à Londres en 1877, sa femme Cosima, la seconde fille de Liszt avec Marie d’Agoult, arrivera avec une lettre d’introduction de son père à Eliot qui deviendra vite une proche de Wagner aussi. (à gauche, Cosima avec son père)

Pendant les quelques mois de leur séjour à Weimar, Eliot deviendra assez intime avec Liszt. Une amitié qui va durer longtemps, car quand Wagner viendra diriger sa musique à Londres en 1877, sa femme Cosima, la seconde fille de Liszt avec Marie d’Agoult, arrivera avec une lettre d’introduction de son père à Eliot qui deviendra vite une proche de Wagner aussi. (à gauche, Cosima avec son père)

1. Les Sabéennes (GOUNOD-LISZT)

La première de l’opéra La reine de Saba de Gounod à l’Opéra de Paris, le 28 février 1862, n’a pas été couronnée comme Faust (1859), ou Roméo et Juliette (1867), de succès triomphal. Néanmoins il a dû plaire suffisamment à Liszt qui, entre 1862 et 1865, a fait cet arrangement du troisième mouvement du ballet de l’acte IV, sc.2.

2. Notturno II – Seliger Tod(Rêve d’amour n° 2)

Conçus à l’origine pour ténor et accompagnement de piano, les 3 Liebesträume, composés en 1850, étaient finalement publiés pour piano seul avec l’addition de textes poétiques dans la page de garde. Pour les deux premières figurent des textes du poète allemand Ludwig Uhland (1787-1862), homme littéraire et politique. Ses séries de Ballades qui figurent parmi ses meilleurs écrits, ont l’aspect de chants populaires:

Gestorben war ich vor Liebeswonne, begraben lag ich In ihren Armen, erwecket ward ich von ihren Küssen, den Himmel sah ich In ihren Augen

J’étais mort de l’extase amoureuse, couché comme une sépulture dans vos bras, quand, réveillé par vos baisers, j’ai vu le ciel dans vos yeux

3. Vallée d’Obermann

Ce chef-d’œuvre faisant partie des Années de Pélèrinage en Suisse, éditées en 1855, est le plus long des neuf morceaux qui rappellent son séjour en Suisse quelques vingt années auparavant avec Marie d’Agoult. Sur la page de garde Liszt fait mettre des extraits de deux œuvres littéraires : Obermann d’Etienne Pivert de Senancour et Childe Harold de Lord Byron.  De Senancour, à gauche, (1770-1846) a été influencé par Rousseau en écrivant son Obermann (1804). Plutôt qu’un roman, son œuvre est une longue complainte sur la dureté de la vie et le désespoir inévitable de l’artiste, malgré les consolations de la nature ou des passions intellectuelles. Un mariage malheureux l’enfonçant dans un pessimisme virulent, de Senancour regrette que sa volonté malade l’empêche de devenir un “surhomme” (le sens de “Obermann”).

De Senancour, à gauche, (1770-1846) a été influencé par Rousseau en écrivant son Obermann (1804). Plutôt qu’un roman, son œuvre est une longue complainte sur la dureté de la vie et le désespoir inévitable de l’artiste, malgré les consolations de la nature ou des passions intellectuelles. Un mariage malheureux l’enfonçant dans un pessimisme virulent, de Senancour regrette que sa volonté malade l’empêche de devenir un “surhomme” (le sens de “Obermann”).

“Que veux-je? que suis-je? que demander à la nature?… Toute cause est invisible, toute fin trompeuse; toute forme change, toute durée s’épuise :…je sens, j’existe pour me consumer en désirs indomptables, pour m’abreuver de la séduction d’un monde fantastique, pour rester atterré de sa voluptueuse erreur.”

Senancour Obermann – Lettre 53

Si je pouvais découvrir et incorporer maintenant tout ce que j’ai au plus profond de moi, – si je pouvais exprimer toutes mes pensées, et ainsi jeter mon âme, mon cœur, mon cerveau, mes passions, mes sentiments, forts ou faibles, tout ce que j’aurais encore cherché et tout ce que je cherche, porte, sais, sens, et même respire, – en un seul mot, et que ce mot soit comme un éclair, je le dirais. Mais les choses étant ce qu’elles sont, je vis et je meurs inentendu, avec une pensée sans voix que je remets en moi comme une épée dans un fourreau. Lord Byron – Childe Harold

Si je pouvais découvrir et incorporer maintenant tout ce que j’ai au plus profond de moi, – si je pouvais exprimer toutes mes pensées, et ainsi jeter mon âme, mon cœur, mon cerveau, mes passions, mes sentiments, forts ou faibles, tout ce que j’aurais encore cherché et tout ce que je cherche, porte, sais, sens, et même respire, – en un seul mot, et que ce mot soit comme un éclair, je le dirais. Mais les choses étant ce qu’elles sont, je vis et je meurs inentendu, avec une pensée sans voix que je remets en moi comme une épée dans un fourreau. Lord Byron – Childe Harold

4. Notturno I – Hohe Liebe(Rêve d’amour n° 1)

Une autre Ballade du poète Uhland (à gauche) ) figure sur la page de garde du premier des Liebesträume. Puisque les deux poètes choisis par Liszt pour ses Rêves d’amour (Uhland et Freiligrath) sont aussi des hommes politiquement très engagés dans le renouveau social de l’époque, et qu’il compose ses morceaux en 1850, après les événements dramatiques de la Révolution de 1848, ne fait-il pas ici allusion plutôt aux rêves brisés de l’amour du prochain qu’à la passion érotique? Ecoutez Liebestraum no 1.

Une autre Ballade du poète Uhland (à gauche) ) figure sur la page de garde du premier des Liebesträume. Puisque les deux poètes choisis par Liszt pour ses Rêves d’amour (Uhland et Freiligrath) sont aussi des hommes politiquement très engagés dans le renouveau social de l’époque, et qu’il compose ses morceaux en 1850, après les événements dramatiques de la Révolution de 1848, ne fait-il pas ici allusion plutôt aux rêves brisés de l’amour du prochain qu’à la passion érotique? Ecoutez Liebestraum no 1.

In Liebesarmen ruht ihr trunken, Des Lebens Früchte winken euch. Ein Blick nur ist auf mich gesunken, doch bin ich alle reich. Das Glück der Erde miss ich gerne und blick, ein Märtyrer, hinan denn über mir in goldner Ferne, hat sich der Himmel aufgetan.

Ivre dans les bras de l’amour parmi les fruits attrayants de la vie, pour un seul regard qui m’a choisi je suis encore toute richesse. Je peux me passer du bonheur terrestre car, martyr, j’élève le regard vers les hauteurs où le ciel révèle des splendeurs dorées.

5. Les Adieux – Rêverie sur un motif de l’opéra de Charles Gounod Roméo et Juliette

Roméo et Juliette, l’un des grands succès de Gounod, fut crée le 27 avril 1867 et Liszt (à gauche) avait écrit cette fantaisie avant la fin de cette même année. La scène des adieux dans l’acte III de la pièce de Shakespeare, est la dernière fois que les amants causeront:

Roméo et Juliette, l’un des grands succès de Gounod, fut crée le 27 avril 1867 et Liszt (à gauche) avait écrit cette fantaisie avant la fin de cette même année. La scène des adieux dans l’acte III de la pièce de Shakespeare, est la dernière fois que les amants causeront:

Romeo : J’ai plus le désir de rester que la volonté de partir. Vienne la mort, et elle sera bien venue !… Comment va-t-elle, mon âme ? Causons, il n’est pas encore jour.

Juliette : Mais si, c’est le jour, c’est le jour ! Fuis vite, va-t’en, pars : c’est l’alouette qui détonne ainsi, et qui lance ces notes aiguës et discordantes… Ô Dieu ! j’ai dans l’âme un présage fatal. Maintenant que tu es en bas, tu m’apparais comme un mort au fond d’une tombe; ou mes yeux me trompent, ou tu es bien pâle.

Romeo : Crois-moi, amour, tu me sembles bien pâle aussi. Le chagrin altéré boit notre sang. Adieu ! adieu !

Liszt se sert de trois motifs de l’opéra de Gounod (et non d’un seul comme son titre l’indique) pour mieux cerner l’esprit global de l’œuvre.

6. Ballade n° 2 en si mineur

Composée en 1853 tout de suite après la Sonate en si mineur, la Ballade n° 2, est aussi une œuvre dramatique d’un seul tenant. Ses trois thèmes principaux sont transformés continuellement par un procédé d’écriture remarquable qui s’imposait déjà dans la Sonate. Liszt, extrêmement  engagé dans la société de son époque, ne pouvait être que profondément ému par les événements de la Révolution de 1848. Beaucoup de ses amis proches y ont péri. Cette œuvre est dédicacée posthumément au comte Karoly Leiningen (à gauche) , exécuté en octobre 1849 avec douze autres chefs de la révolte hongroise. Sacheverell Sitwell a dit de cette pièce qu’elle évoquait pour lui: “de grands événements de l’ordre héroïque, des invasions barbares, des cités en flammes – des tragédies d’intérêt plus publique que privé.”

engagé dans la société de son époque, ne pouvait être que profondément ému par les événements de la Révolution de 1848. Beaucoup de ses amis proches y ont péri. Cette œuvre est dédicacée posthumément au comte Karoly Leiningen (à gauche) , exécuté en octobre 1849 avec douze autres chefs de la révolte hongroise. Sacheverell Sitwell a dit de cette pièce qu’elle évoquait pour lui: “de grands événements de l’ordre héroïque, des invasions barbares, des cités en flammes – des tragédies d’intérêt plus publique que privé.”

7. – 12. Consolations

Les six pièces des Consolations, composées vers 1850, imbues d’une mélancolie et d’une dévotion fervente, ont été inspirées par un recueil de poèmes de Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve (1804-1869) du même titre, publié anonymement en 1830. Sainte-Beuve s’était intéressé, comme Liszt, aux principes socialistes du saint-simonisme et avait mis beaucoup d’espoir dans le renouveau du catholicisme libéral. Mais après la bulle papale de 1832 réprimant ce renouveau, Sainte-Beuve, déçu, va s’éloigner de l’église pour prendre progressivement part à la politique. En écrivant ses Consolations, Liszt affiche vingt ans après, son admiration pour le personnage de Sainte-Beuve.

13. Notturno III- O Lieb(Rêve d’amour n° 3)

Le troisième des Liebesträume est accompagné d’un texte du poète Ferdinand Freiligrath (1810-1876). Quand George Eliot a rencontré Liszt, ils ont communiqué en français. Eliot avait  commencé sa carrière littéraire avec des traductions de l’allemand vers l’anglais. Freiligrath (à gauche) était le traducteur d’Alfred de Musset et de Victor Hugo, comme de Tennyson et de Longfellow. Politiquement actif, il a collaboré avec Karl Marx au journal Neue Rheinische Zeitung dans le Cologne de 1848. Mais en 1849 il était exilé de Cologne suite à la censure du journal. Liszt n’aurait pas pu ignorer ces faits au moment de la publication de ses Rêves d’amour en 1850.

commencé sa carrière littéraire avec des traductions de l’allemand vers l’anglais. Freiligrath (à gauche) était le traducteur d’Alfred de Musset et de Victor Hugo, comme de Tennyson et de Longfellow. Politiquement actif, il a collaboré avec Karl Marx au journal Neue Rheinische Zeitung dans le Cologne de 1848. Mais en 1849 il était exilé de Cologne suite à la censure du journal. Liszt n’aurait pas pu ignorer ces faits au moment de la publication de ses Rêves d’amour en 1850.

O lieb, o lieb so lang du lieben kannst, so lang du lieben magst. Die Stunde kommt, wo du an Gräbern stehst und klagst und sorge dass dein Herz glüht, und Liebe hegt une Liebe trägt. So lang ihm noch ein ander Herz in Liebe warm entgegenschlägt, und wer dir seine Brust erschliesst, o tu ihm was du kannst zu lieb und mach ihm jede Stunde froh, und mach ihm keine Stunde trüb! Und hüte deine Zunge wohl : bald ist ein hartes Wort entflohn. O Gott – es war nicht bös gemeint – Der andre aber geht und weint.

Aime, aime, aussi longtemps que tu puisses, aussi longtemps que tu en aies envie. Car l’heure arrive où tu te plaindras d’être enfermé dans la tombe. Veille à ce que ton cœur soit toujours ardent, qu’il sente, qu’il supporte, aussi longtemps qu’un autre cœur vient se chauffer de ton amour. Et quiconque t’ouvre son cœur, donne-lui ce que tu peux d’amour, et crée chaque heure de nouvelles joies pour lui, ne le rends jamais triste! Et garde bien ta langue : une parole dure est si vite échappée. Oh mon Dieu – ce n’était pas dit pour faire du mal. Mais déjà l’autre est parti en pleurant.

14. Hymne à Sainte Cécile (GOUNOD-LISZT)

En 1848, après avoir étudié la théologie pendant cinq ans, Charles Gounod (1818-1893) était sur le point d’entrer dans les ordres. En 1861, Liszt, mécontent d’une certaine hostilité de la part de groupes conservateurs à Weimar, quitte son poste pour s’installer à Rome et prend les ordres mineurs. Voici une œuvre dédiée à la sainte patronne de la musique où les marques de tous les  deux sont évidentes. Gounod (à gauche) avait écrit l’original, une pièce pour violon et piano, en 1865. Liszt finit sa transcription le 3 juin 1866, créant un morceau de 160 mesures à partir des 77 mesures de Gounod. Sans doute Liszt avait-il l’intention de faire publier cette partition mais il dût la lui laisser échapper, car il écrit dans une lettre du 20 janvier 1885, adressée de Rome à la comtesse Mercy-Argenteau: “Un éditeur obstiné m’a redemandé ma transcription de Sainte Cécile de Gounod. Si vous pouviez trouver son manuscrit parmi vos vieux papiers, soyez aussi aimable de me le prêter pendant quinze jours pour que ceci puisse être copié, imprimé et puis retourné à sa propriétaire charmante.” Le manuscrit qui n’était pas trouvé à temps (Liszt est mort l’année d’après) n’a été publié que récemment dans la nouvelle édition compréhensive des œuvres de Liszt de Budapest.

deux sont évidentes. Gounod (à gauche) avait écrit l’original, une pièce pour violon et piano, en 1865. Liszt finit sa transcription le 3 juin 1866, créant un morceau de 160 mesures à partir des 77 mesures de Gounod. Sans doute Liszt avait-il l’intention de faire publier cette partition mais il dût la lui laisser échapper, car il écrit dans une lettre du 20 janvier 1885, adressée de Rome à la comtesse Mercy-Argenteau: “Un éditeur obstiné m’a redemandé ma transcription de Sainte Cécile de Gounod. Si vous pouviez trouver son manuscrit parmi vos vieux papiers, soyez aussi aimable de me le prêter pendant quinze jours pour que ceci puisse être copié, imprimé et puis retourné à sa propriétaire charmante.” Le manuscrit qui n’était pas trouvé à temps (Liszt est mort l’année d’après) n’a été publié que récemment dans la nouvelle édition compréhensive des œuvres de Liszt de Budapest.

REMERCIEMENTS

Ingénieur du son: Karim Saï, grâce à Caravan

Enregistré en 24 bits au Studio de Didier Lockwood à Barbizon

Merci à Didier et Caroline, Karim et surtout à Simonne

Dédié à Shirley and Jim, plus de 60 années ensemble

Textes de présentation et traductions par Jeffrey Grice